Over the years I’ve spoken to hundreds of people who have attempted some kind of collaborative online work only to have it go sideways. It happens to me, too. It’s pretty common, since tools for remote collaboration are not yet a completely solved problem.[1]

What struck me in these conversations is the commonality of feeling that people express when they tell me about the problems they’ve had. They’re understandably frustrated, sure, but there’s also a sizable chunk of disappointment and betrayal in the mix: My tools let me down, and I feel personally hurt.

It’s totally natural to feel this way. It comes about in part because we unconsciously expect the technology to take away some of the burden of whatever we’re doing, the way a word processor takes away some of the burden of typing with spelling correction, easy undo, delete, and cut and paste. We expect that the technology will bear some of the burden of designing, planning, running, and facilitating the remote work we need to do. We certainly expect it to help connect people who are located at a distance from each other. We expect the work, therefore, to be easier. And then we try it, and it isn’t, and we feel let down.

The truth is, in the world of remote collaboration, technology doesn’t make anything easier. Technology just makes some things possible that aren’t otherwise possible.

It’s not actually supposed to be easier; as I said, the tools aren’t there yet. But based on experiences with older technologies that are solved problems, like telephones and word processors and spreadsheets, we imagine it should be easier to get people together online and have a meeting and get real work done, and we feel disappointed and betrayed when it isn’t.

So how can we address this issue? During those conversations with disappointed remote workers, I asked why the work felt so painful. Their responses resolved into three major problems that came up again and again. The bad news is, these problems make remote work a struggle. The good news is, they are fixable, though not with a purely technical solution.

The three problems that make remote work so much harder boil down to these:

- The structure of the engagement doesn’t match the intended outcomes.

- The collaborative bandwidth we expect to be available to us, is reduced.

- People don’t feel co-present with one another, and instead feel disconnected.

Let’s look at how each one shows up and what you can do to fix it in your next remote engagement.

Problem 1: The structure of the engagement doesn’t match the intended outcomes.

This causes frustration because people can’t do the work they have shown up to do, which is very unsatisfying. The fix is straightforward and can be implemented even before the engagement starts, although I am always ready to pivot during an engagement if it turns out I goofed in my planning.

When designing a remote engagement, carefully think through what you want to accomplish in a given period of time, and how you can best use that time to get to your outcomes. It takes more time and more thought than preparing for a similar face-to-face meeting, but the work itself is not all that different.

These are the questions I ask myself to make sure the structure is going to match the outcomes of my remote engagement:

- What does this group need to accomplish before the engagement ends?

- Are they also invested in those outcomes? If not, what do I need to do to either realign the outcomes or increase people’s investment in them before we start?

- What is the highest and best use of our time together? The phrasing of this question comes from my colleague Marsha Acker, CEO of TeamCatapult, and I love how it helps me prioritize what should be done together and what can be done asynchronously (or not at all).

- When I imagine each participant sitting alone at their computer, what can I offer that will help them accomplish the outcomes they are invested in? Here, I’m thinking about activity design, tools, careful instructions, smooth transitions, and tech support, but I’m also thinking about the attitude or presence that I will bring to the group — calm and supportive.

- How am I going to make sure no one gets lost when we switch from one tool or context to another? What am I going to do when someone gets lost anyway?

- How long can I expect them to focus on this engagement? Is that enough time to accomplish all the outcomes? If not, what do I need to change about my design?

There are two reasons this takes longer for a remote engagement than a face-to-face one: most of us aren’t used to doing complex remote engagements, so we have to think about it more than we would if it were a face-to-face engagement; and the toolset is wider and requires more research than the familiar in-room toolset. Both of those things do get easier with time and practice.

Problem 2: The collaborative bandwidth we expect to be available to us, is reduced.

We’re all aware that there are many rich communication channels available to us when we are standing face-to-face with someone, especially if we’re in a well-appointed meeting space with tools to support the work that needs to be done. When we switch to an online setting, we are also acutely aware that many of those channels have been stripped away; the most common one that people miss is body language, but it’s not the only compromised channel. I call those channels, and the capacity they have to enable communication, collaborative bandwidth.

Collaborative bandwidth is defined as the number of channels available to support collaborative group work and the capacity of those channels to enable communication in the service of that work. (p. 24)[2]

Imagine the amount of communication your group has to have in order to accomplish its outcomes. Imagine all that communication moving through a wide pipe, big enough with room to spare. No problem. Now imagine the pipe gets smaller — a lot smaller. Like 80% smaller. Communication slows down, mushes together, and becomes unclear and frustrating. That’s exactly what’s happening in a remote engagement that doesn’t have enough collaborative bandwidth.

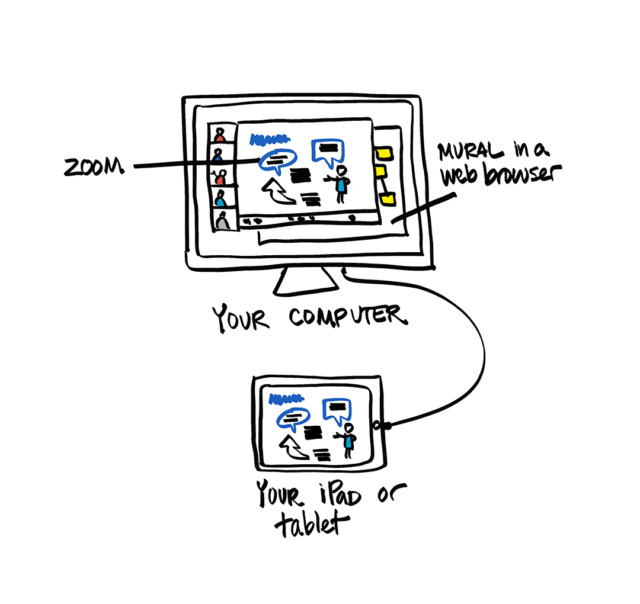

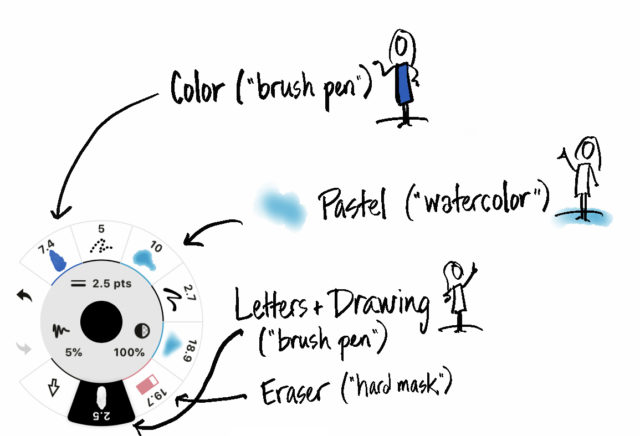

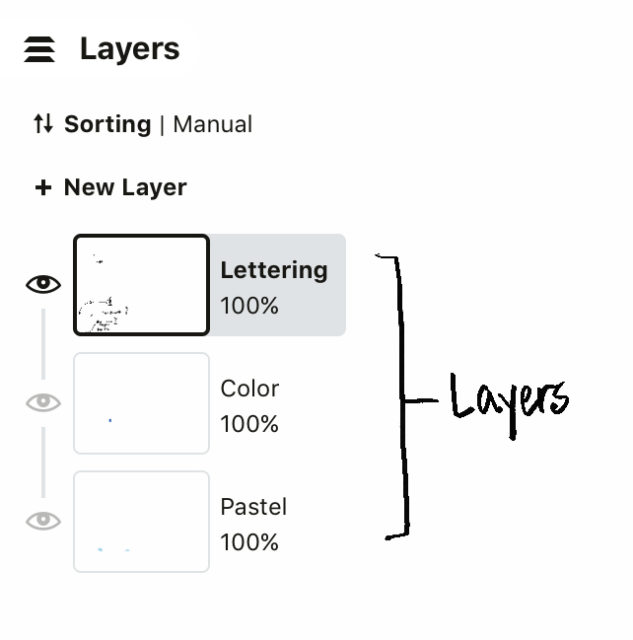

The fix is simply to make the pipe bigger: add enough collaborative bandwidth to accomplish what needs to get done. Audio is one channel, video is another, sharing screens is a third, and using hands-on tools to co-create something is a fourth (there are many others). If your design includes enough channels to support the work you are doing, you can reduce this pain point or remove it entirely. I usually use different channels throughout an engagement depending on what we’re doing at the time. (See footnote #2 if you want to get geeky with collaborative bandwidth.)

Problem 3: People don’t feel co-present with one another, and instead feel disconnected.

Co-presence is the feeling of being somewhere together with someone. I learned about it from Rachel Hatch, who was at the Institute for the Future at the time. She was exploring technologies to support co-presence and the idea of replacing telepresence, where you are present on video and audio, with co-presence, where you are present in other ways as well. The concept has stuck with me and influenced the way I plan my remote engagements ever since. I find that people who feel co-present are more productive and effective at collaborative work than people who don’t feel co-present.

To really bring this concept home, think about attending a webinar where you have no idea who else is there, or even how many attendees there are. The audio only supports the speaker or panelists; the only visuals you see are the ones they choose to share. It feels like you are alone on one side of a one-way mirror. During Q&A, you find out that some people you know are also attending, but you have no opportunity to connect with them. This is the opposite of co-presence. It might be a good way to deliver a lecture, but it’s a terrible way to do collaborative work.

Now think about a virtual coffee break with your best friend or a close family member. It’s just the two of you, your video connection is working great, the audio is clear, and you each have your favorite hot beverage in hand. You sip and laugh and comfort each other about whatever you’re struggling with at the moment. This is absolutely co-presence. Although it’s a social example, this is the feeling that will help people work together better remotely.

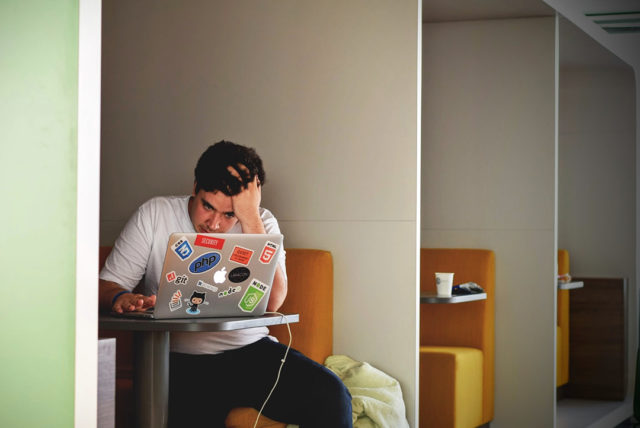

Photo by Brooke Cagle on Unsplash

To bring co-presence into a remote engagement, I ask myself this question as I’m preparing for it: What approaches and tools will work best for this group in this situation to increase their sense of co-presence? The answer will be different depending on the size of the group, who is in it, and what you all need to accomplish together.

Here are some of the ways I do it:

- Request (coax, if necessary) that people use a video camera for conversations that are personal in nature, like check-ins and check-outs.

- Ask people to choose a photograph, either one of theirs or one that they like from a site like Unsplash, and share it while they tell us briefly why they chose it. (I use this as an icebreaker, or right after a break in a longer engagement.)

- Set up small breakout groups so people can connect with a few other people while they work, rather than always being in a large group. Mix up the breakouts for different activities.

- Establish a chat backchannel and encourage people to use it while working (yes, even in a meeting) if they have questions, off-topic ideas, or just want some individual connection.

- Let go of the feeling that I need to control every interaction in order to stay “in charge,” and accept that technology can mediate interactions that I’m not party to — and don’t need to be party to. In other words, allow people to whisper behind my back.

These are just a few of the many solutions to this problem. Once you begin to think about helping people create a sense of co-presence, it changes the way you structure the engagement and the way you show up online.

I try always to plan for and to consider all three of these common problems when designing a remote engagement. I hope this helps you create engagements that connect and inspire you and the people you work with.

Footnotes

[1] That is to say, they are not yet as invisible and reliable as the landline telephone, which could be used by anyone whether or not they had any understanding of how it worked. You still need to know too much about remote collaborative tools for them to be truly comfortable yet.

[2] Smith, R. (2014). Collaborative bandwidth: creating better virtual meetings. Organization Development Journal, 32(4), 15-35. An excerpt of the article is available on The Grove’s website. The link on that page to download the full article no longer works, but libraries and scholarly databases usually include OD Journal.